Molly Allen is a 2023 Florida Sea Grant Coastal & Marine Sciences Research Intern. She is a University of Florida student pursuing a bachelor’s degree in sustainability studies and economics with a minor in international development & humanitarian assistance.

Allen participated in field work to learn more about spat monitoring and recruitment for Eastern oysters. Image courtesy of Molly Allen.

Florida’s coastal ecosystems, teeming with life and vitality, serve as critical hubs for both biodiversity and human livelihoods. Among the many critical components of these ecosystems, the Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica), stands out as a remarkable keystone species. Unfortunately, native oyster populations have faced considerable decline in recent years due to factors such as disease, poor water quality and over harvesting.

Consequently, oyster reef restoration and enhancement projects have gained significant attention due to their ecological benefit and potential to improve coastal resilience. To enhance the effectiveness of these efforts, understanding oyster reproduction and spat recruitment patterns is crucial. Enter the Florida Spat Monitoring Network, an initiative that aims to shed light on these essential aspects of oyster restoration.

After approximately two weeks living in the water column, oyster larvae require suitable substrate to settle on and grow into adult oysters. At this early stage they are called spat. Oyster restoration projects often involve introducing substrate in order to foster spat recruitment. However, the availability of oyster larvae for recruitment varies, and the timing of their settlement is seasonal, presenting challenges for restoration practitioners. While seasonal variations in oyster reproduction are well known, this project aims to unveil when the peak of spat recruitment occurs in different areas, as well as whether recruitment occurs in discrete seasonal peaks or if there is also a continuous low level of spat settling throughout the summer months.

From trudging through marshy shores to peering at barnacles under a microscope, I’ve developed a much deeper appreciation for the complexity of life on our coasts.

Molly Allen

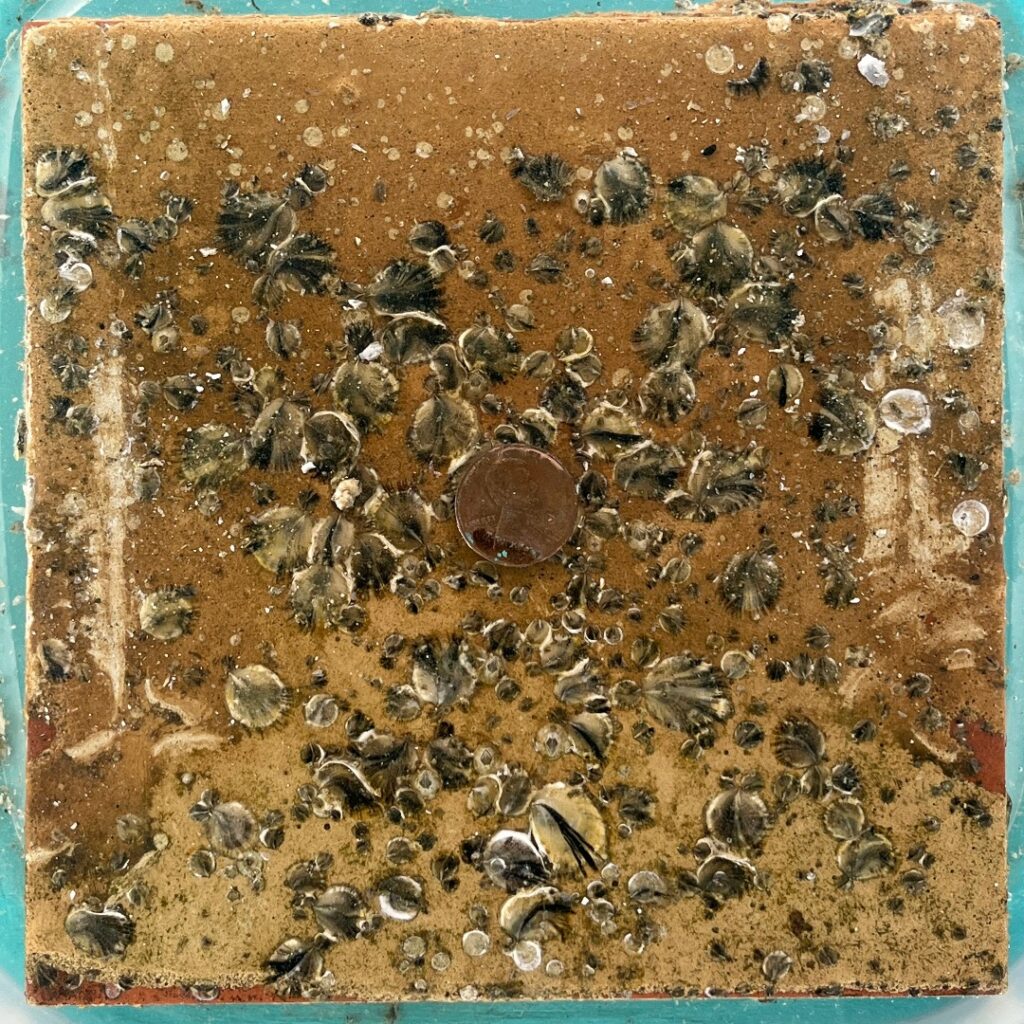

Artificial oyster substrates used to monitor spat recruitment. Image courtesy of Molly Allen.

This summer, I worked with Dr. Mark Clark, a Florida Sea Grant affiliate from the UF/IFAS Soil, Water, and Ecosystem Sciences Department, to develop a spat monitoring protocol. Working at the Nature Coast Biological Station in Cedar Key, I have been deploying artificial oyster substrates in the form of 6-inch square tiles to monitor spat recruitment. Starting May 2, 2023, we have deployed a set of new tiles every two weeks while the previous set is photographed and analyzed to determine the number of spat that settled within the previous period. If the results of the summer pilot monitoring effort look promising, the ultimate goal of the project is to expand into a volunteer-based citizen science initiative. By recruiting other sites throughout Florida to participate in the monitoring program, we hope to establish a collective database that provides region-specific oyster spat settling patterns.

Aside from working on this spat monitoring project, I have also had the opportunity to work on other shoreline restoration projects within Dr. Clark’s lab, which has worked with Nature Coast Biological Station to implement living shorelines in Cedar Key as a comprehensive approach to coastal protection, habitat restoration, and climate adaptation. As part of my internship this summer, I got to participate in the lab’s yearly assessment of these living shorelines by conducting elevation, vegetation, and wildlife surveys. I counted so many snails and crab burrows! It was very fascinating to see the difference in the biota of a living shoreline compared to a traditional shoreline.

Fieldwork and scientific research have been an adventure filled with challenges and rewards. From trudging through marshy shores to peering at barnacles under a microscope, I’ve developed a much deeper appreciation for the complexity of life on our coasts. I also learned that environmental solutions are not just scientific endeavors; they must consider the interactions of social, economic, and environmental factors. This experience has shown me how to approach things with a holistic perspective, seeking sustainable solutions that benefit both nature and society. Through my work this summer and beyond, I hope to contribute valuable insights to the field of coastal restoration and support the preservation of these habitats for generations to come.